Why are Liberal Professors More Conservative on Campus?

It has to do with motivated reasoning.

University professors like myself are on the political left by a large margin. We champion government intervention to solve society’s problems, favor top-down policies to regulate industries, and trust bureaucrats to ensure fairness and safety. But when it comes to our own workplaces, we suddenly sound rather… conservative.

We bristle at administrative mandates, lament bureaucratic inefficiency, and insist that centralized decision-making undermines expertise and autonomy. We defend long-standing academic traditions and resist rapid institutional change, despite advocating for progressive overhauls in the broader world.

A double standard seems to be lurking: resistance to bureaucracy and change when it affects us directly, but endorsement of those very same forces in other sectors. What explains this apparent inconsistency?

Tradition Inside, Revision Outside

Consider tradition first. In public policy, liberals often push to discard long-standing institutions they see as outdated or unjust. They advocate defunding the police, abolishing the electoral college, and dismantling fossil fuel dependence. They argue that historical monuments should be torn down along with gender norms.

Yet within our own institutions, professors often act as staunch defenders of tradition. We balk at proposals to change tenure and other protections of academic freedom, despite potential costs to accountability. We often resist efforts to restructure departments, revise general education curricula, or implement standardized assessment measures. Few professors willingly embrace new technologies or teaching strategies, such as online learning, AI writing tools, and competency-based education that allows students to learn at their own pace.

The same pattern appears when we turn from teaching to research. We now live in a world of digital media, yet many scholars are wary of new online-only journals and value those with a venerable history. Despite a crisis of confidence in science, we resist proposals to overhaul how we conduct, review, and publish research. In response to failures to replicate studies in a wide range of fields, some researchers have proposed a more demanding threshold of statistical significance (e.g., p < .01 instead of p < .05). It hasn’t caught on. Although some reforms have become more common—such as sharing data on public repositories and preregistering hypotheses—these practices have been met with a surprising level of resistance among people who swiftly embrace gender-neutral pronouns and the inclusion of trans women in competitive sports. On campus, professors act like the kind of traditionalists we deride elsewhere.

What’s concerning isn’t the progressive politics but rather the potential inconsistency. A core principle of reasoning calls on us to treat like cases alike—or else identify a relevant difference. Some might argue that academic traditions are more worth preserving because they safeguard knowledge production in ways that other societal traditions do not. But this argument smacks of elitism, assuming as it does that academic traditions are more fair and venerable.

In reality, both academia and society contain traditions worth keeping and others worth reconsidering. If faculty critique stubborn resistance to change in broader culture, they should be open to the same critique within their own profession. Or, if it is truly risky to overhaul time-honored traditions within academia, perhaps similar costs beyond the ivory tower should be more readily acknowledged (Chesterton’s fence and all that). The stability, unity, and shared history that traditions provide arises partly from their form as widely held norms, not their particular content. Oddly enough, we often hear within the walls of academia a valorizing of Western intellectual history simply because it is “our” shared history. Perhaps that’s problematically colonial. Or, if it’s on to something, then there may be more merit to similar ideas about long-standing norms in society.

Bureaucracy is Good, Except in Universities

Another potential double standard arises in how professors regard bureaucracy. Progressive professors often argue that broad, top-down policies are necessary to address systemic problems. In public life, liberals support government intervention to ensure fairness and prevent exploitation. They champion workplace regulations to protect employees, environmental policies to curb corporate excess, and labor laws that impose minimum wages and benefits. These policies may limit the autonomy of businesses and professionals, but they will surely serve the greater good.

In universities, however, faculty champion shared governance and complain about bureaucratic oversight. We frequently grumble about the ever-expanding list of required syllabus statements, viewing them as intrusive and unnecessary. Faculty members bemoan how administrative offices impose rigid metrics, compliance training, and mandatory assessment reporting. In hallways one often hears that administrators should simply trust us to do our jobs, much as farmers and business owners argue against excessive government regulation.

Beyond teaching, research is likewise constrained by a maze of rules amid mountains of paperwork. Many researchers (myself included) lament the inefficiencies of ethics review boards, which they see as slow and overly cautious barriers to research with humans and other animals. Those of us who chase after grant funding spend nearly as much time navigating red tape as we do conducting the research.

We also complain about wasteful spending with administrative bloat. Just to order T-shirts for students in our programs, it may take months to navigate the complicated branding rules and the various administrators who seem unable to agree on whether the proposed design is in compliance. When a university goes through a rebranding, we balk at the millions of tuition dollars wasted on consulting firms, materials, and labor—just to slightly change every logo and piece of letterhead across campus. Despite widespread support among faculty for promoting diversity in general, most regard diversity (DEI) training as a waste of time and money.

What might justify a double standard?

(1) One possible defense is that professors are experts in their fields and should be trusted to self-regulate. In contrast, builders, business owners, and venture capitalists may be driven by profit, which conflicts with society’s best interests.

But expertise is hardly unique to academia. Farmers, engineers, and entrepreneurs also possess specialized knowledge that is often neglected by bureaucrats who overestimate their own ability to intervene rather than impede. As Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson have detailed in their book Abundance, California’s high-speed rail project remains tangled in red tape with unintended consequences:

Trains [produce fewer emissions] than cars, but high-speed rail has had to clear every inch of its route through environmental reviews, with lawsuits lurking around every corner. The environmental review process began in 2012, and by 2024 it still wasn’t finished. […] What has taken so long on high-speed rail is not hammering nails or pouring concrete. It’s negotiating. Negotiating with courts, with funders, with business owners, with homeowners, with farm owners.

While the profit motive does need some guardrails, us professors aren’t immune to self-interest either. Many defend practices that serve their own convenience rather than the best interests of students, research participants, or the broader community. In addition to resisting new teaching strategies and technologies that could improve student learning, researchers are capable of engaging in fraud and questionable research practices to secure competitive grants or prestigious awards. If we’re being honest, academia, like any profession, contains a mix of high-minded ideals and self-serving tendencies.

(2) Another defense is that the stakes are lower on campus. Societal problems involve life, death, and health, which justify some inefficiencies and sacrifices in autonomy. Think about universal healthcare. The progressive position is that innocent people are suffering, even dying, from lack of health insurance, and through no fault of their own. Sure, Medicare-for-all would be a massive, expensive bureaucracy, but that’s the price to pay for saving people’s lives and livelihood against ruthless, profit-driven health insurance companies.

However, higher education can involve the very same exploitation and discrimination that threatens the rest of society. The role of review boards and compliance training are precisely to protect human subjects and college students from harm and unfair treatment. The desire to produce scientific results has led to many unethical experiments. Government-funded researchers neglected and misled participants in the Tuskegee syphilis study, turned a Stanford basement into a makeshift prison, and created torturous conditions for the Silver Spring monkeys in Maryland. Sadly, textbook examples like these aren’t a thing of the past. Mistreatment, neglect, and exploitation can and do still arise from experiments approved by review boards at world-class universities.

Besides, even if the stakes are often lower on campus, a double standard remains for high stakes cases. There remains a curious trust and confidence in government agencies while exuding distrust and even contempt for the administrations that govern our own workplace. Even when the stakes are equally high or equally low, progressive professors rarely acknowledge that government bureaucracy can be just as inefficient and tyrannical as university administrations.

Recognizing Our Own Biases

What’s going on here? The tension between conservatism for work and progressivism for society may stem in part from motivated reasoning. Rather than applying a consistent set of principles, we might tend to favor top-down solutions to problems only when they don’t constrain our personal and professional lives. When government bureaucracy regulates businesses, it is seen as necessary oversight; when university bureaucracy regulates professors, it is seen as meddlesome interference. When political traditions hinder progressive policies, they are considered outdated; when academic traditions provide stability, they are regarded as essential.

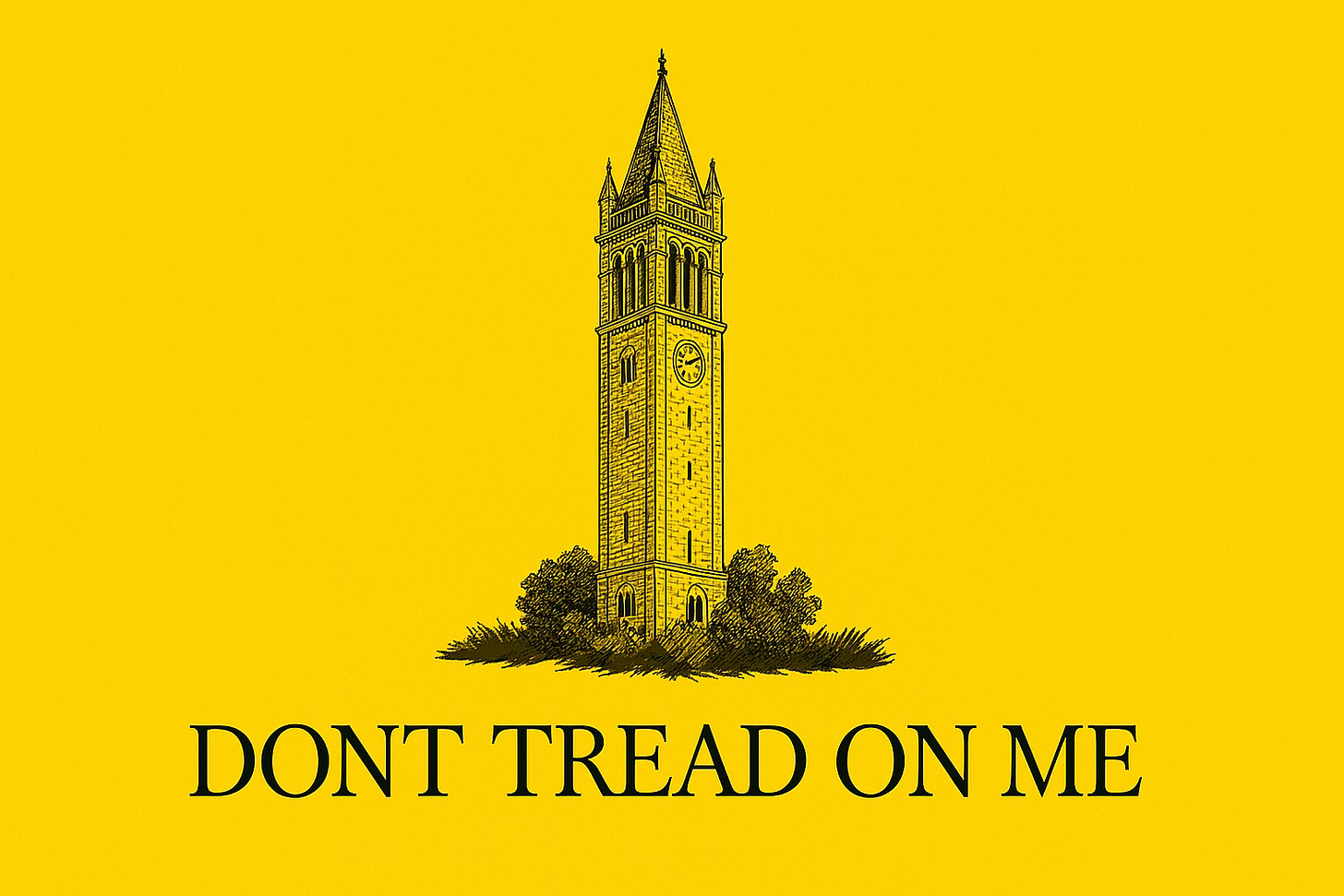

This is not unique to academia. Many professions and industries argue for special treatment when they’re the ones affected. Business leaders demand deregulation while benefiting from government subsidies. Conservative voters tell Uncle Sam “don’t tread on me” while applauding efforts to heavily regulate women’s bodies or ban lab-grown meat. Politicians decry government overreach while defending the bureaucratic complexities of their own offices. The broader lesson is that everyone—including conservatives—should be wary of political inconsistencies.

None of this means that professors should embrace all administrative policies in universities or abandon their political commitments outside them. It does mean that we should be more reflective about the principles we apply across different domains. If we believe bureaucratic oversight is essential for businesses and public institutions, we should consider why we resist it in academia—or else heed calls for smaller government and deregulation in other industries. If we think traditions should not be blindly upheld in society, we should examine why we defend them in universities—or else take more seriously calls for stable traditions elsewhere.

The goal is not to prescribe a particular stance but to encourage consistency in how we evaluate bureaucracy, tradition, and autonomy across different contexts. Academics pride themselves on critical thinking and intellectual virtues. But intellectual honesty demands that we recognize when we are applying principles selectively—favoring autonomy when it suits us and regulation when it constrains others. If we ask society to rethink its assumptions about governance and tradition, we should be willing to do the same within our own halls.

Note: A version of this essay was originally posted on Daily Nous, a blog dedicated to the profession of philosophy. I’m posting a slightly updated version here with permission.

Yep

This was one of Robert Conquest's laws: "Everyone is a conservative about the things he knows best"